By: Joseph Thibault, Cursive Technology

Check out “Biometric Key Logging in Authentic Learning Environments: Introducing the ‘Cursive’ Standard and Collection Tools” by Joseph Thibault and Anissa Sorokin, published in the Journal of Writing Analytics, vol. 7

Disclaimer: Cursive technology is a partner of Open LMS, owner of eLearn Magazine. Learn more

As the new year approaches, whether you’re teaching online or on campus, classrooms will be full of nervous excitement and expectations for learning, work, and achievements in the coming year.

Among the many lingering questions that remain for both students and educators, the most critical may be related to how generative AI continues changing writing in the classroom. Consensus suggests that we can no longer focus on the submission or product of writing alone. AI is more capable of turning out better-looking essays, which are harder to detect, with little effort by the “creator.”

Without a multifaceted approach and frank conversations, students will continue to leverage AI for static text creation.

This year, millions of students on and off campus will navigate a hodgepodge of academic integrity policies, guidelines, requirements, and prohibitions related to AI use in the classroom. From college to college, building to building, department to department, classroom to classroom, and assignment to assignment, students may find themselves constantly revising their use of workflow and productivity tools that they’ve been using for years (months or days) with a constant risk of landing in a tough conversation, getting flagged by a AI detector, or even finding themselves at the wrong end of a AI-usage violation.

Since the introduction of web-based tools like Google and Wikipedia, assignment guidelines and syllabus policies have helped students and teachers alike ensure expectations are met. But after ChatGPT and other generative AI tools, there has been a plethora of policies, frameworks, guardrails, and suggestions to help clarify what it means to work, learn, create, and in our particular case, writing, in a new normal where artificial intelligence can produce academic quality-looking work so easily.

As you tackle these questions head-on, it’s worth looking at the trailblazing other institutions and educators have already done to promote transparency and flexibility.

None or some? How schools are managing AI in writing

Following the launch of ChatGPT, many institutions reacted quickly to update their academic honesty policies and provide faculty with some boilerplate language to include in their syllabus policies to share with students.

We believe most institutions today have AI policies in place to allow faculty to take responsibility for their courses, but institutions have rarely adopted a complete prohibition or the wholesale embrace of AI. At the time of writing, there is no reliable surveys of policy adoption among institutions.

The following is a sample of policies aiming to reflect the diversity of options seen around the world.

University of Sydney’s binary lanes approach

It focuses on types of assessments through an analogy of a two-lane highway. “Lane 1” refers to the student’s own skills, which should be developed independently from AI. “Lane 2” focuses on the use of AI responsibly in guided practice.

| Lane 1 AssessmentsSkills mastered by students, supervised and designed for the ‘assessment of learning’ | Lane 2 AssessmentsSkills related to the use of AI and responsible participation in an AI-integrated society |

| In-class contemporaneous assessment e.g. skills-based assessments run during tutorials or workshopsViva voces or other interactive oral assessmentsLive simulation-based assessmentsSupervised on-campus exams and tests, used sparingly, designed to be authentic, and for assuring program rather than unit-level outcomes | Use of AI to suggest ideas, summarize resources, and generate outlines/structures for assessments.Use of AI-generated responses as part of their research and discovery process. Use of AI to help them iterate over ideas, expression, opinions, analysis, etc.Students design prompts to have AI draft an authentic artifact (e.g. policy briefing, draft advice, pitch deck, marketing copy, impact analysis, etc) and improve upon it. |

University of South Wales Six-Lane Approach

UNSW expands on the highway analogy to include more nuance and specific guidance. The six-lane approach provides something akin to the AI Assessment Scale using a table-based form:

| 1 | NO ASSISTANCE: | This assessment is designed for you to complete without the use of any generative AI. |

| 2 | SIMPLE EDITING ASSISTANCE: | In completing this assessment, you are permitted to use standard editing and referencing functions in the software you use to complete your assessment. |

| 3 | PLANNING/DESIGN ASSISTANCE: | You are permitted to use generative AI tools, software or services to generate initial ideas, structures, or outlines. |

| 4 | ASSISTANCE WITH ATTRIBUTION: | This assessment requires you to write/create a first iteration of your submission yourself. You are then permitted to use generative AI tools, software or services to improve your submission. |

| 5 | GENERATIVE AI SOFTWARE-BASED ASSESSMENTS: | This assessment is designed for you to use generative AI as part of the assessed learning outcomes. |

| 6 | NOT APPLICABLE: | Generative AI is not considered to be of assistance to you in completing this assessment. |

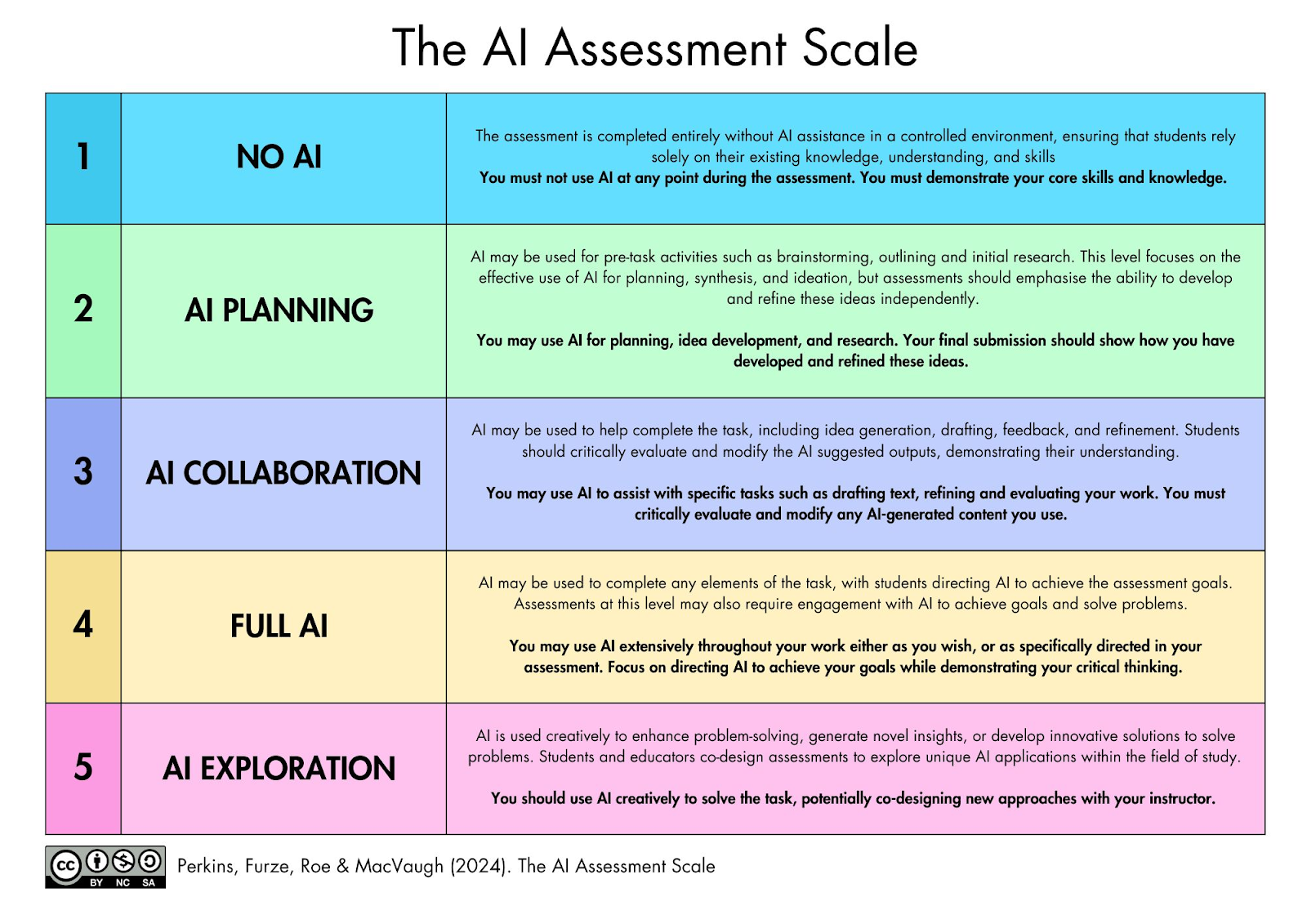

Perkins, Furze, Roe and MacVaugh’s AIAS

The Artificial Intelligence Assessment Scale (AIAS), a framework widely adopted primarily across North American institutions, was created by Mike Perkins, Leon Furze, Jasper Roe, and Jason MacVaugh. First published in August 2023, it has been updated based on feedback from practitioners.

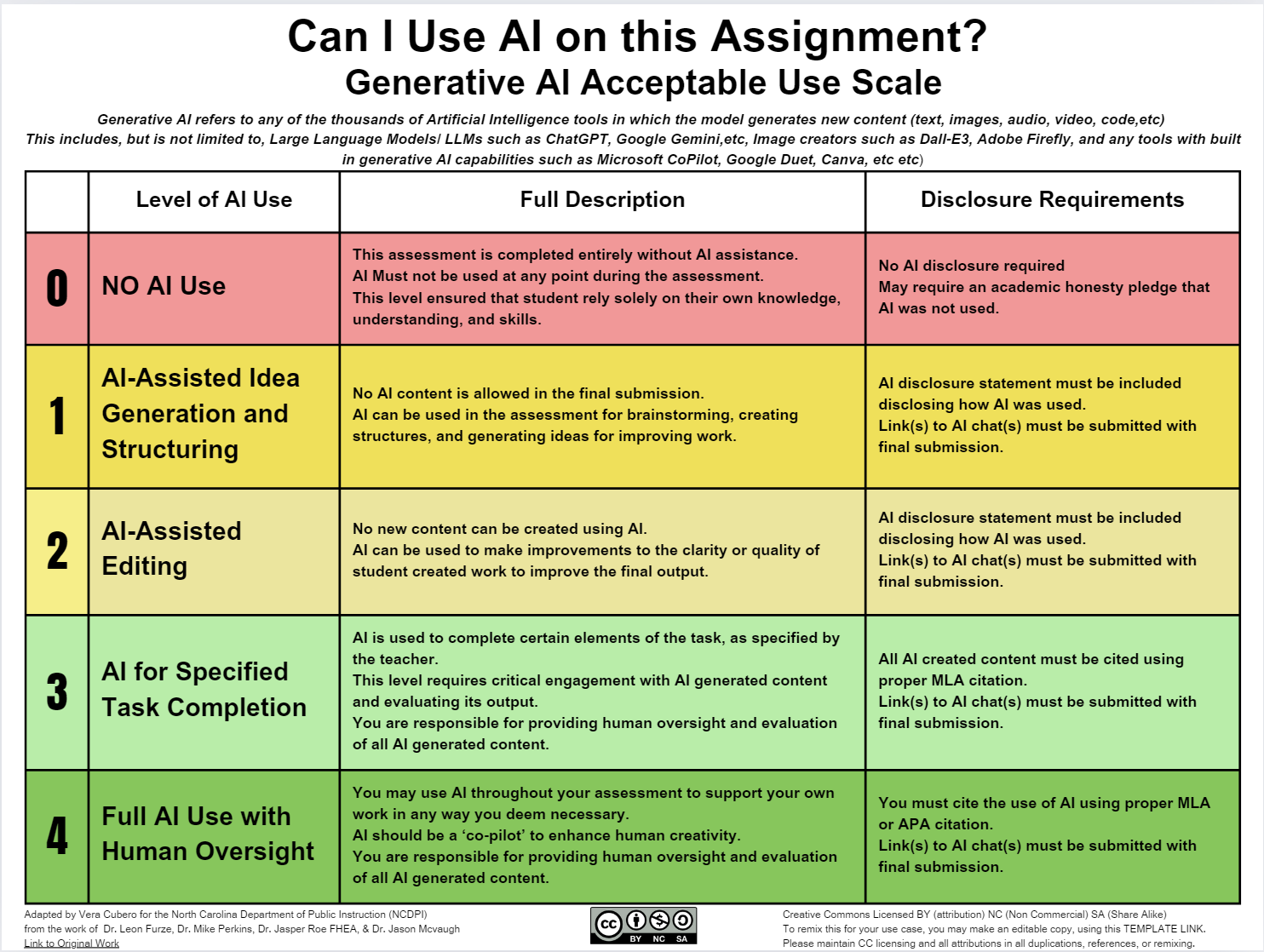

NCDPI’s Acceptable Use Scale

Vera Cubero, Emerging Technologies Consultant for the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI) has done some work to localize and adapt AIAS.

Cubero adds disclosure requirements to the framework, and aims to provide both richer detail and a more intuitive idea of each tranche.

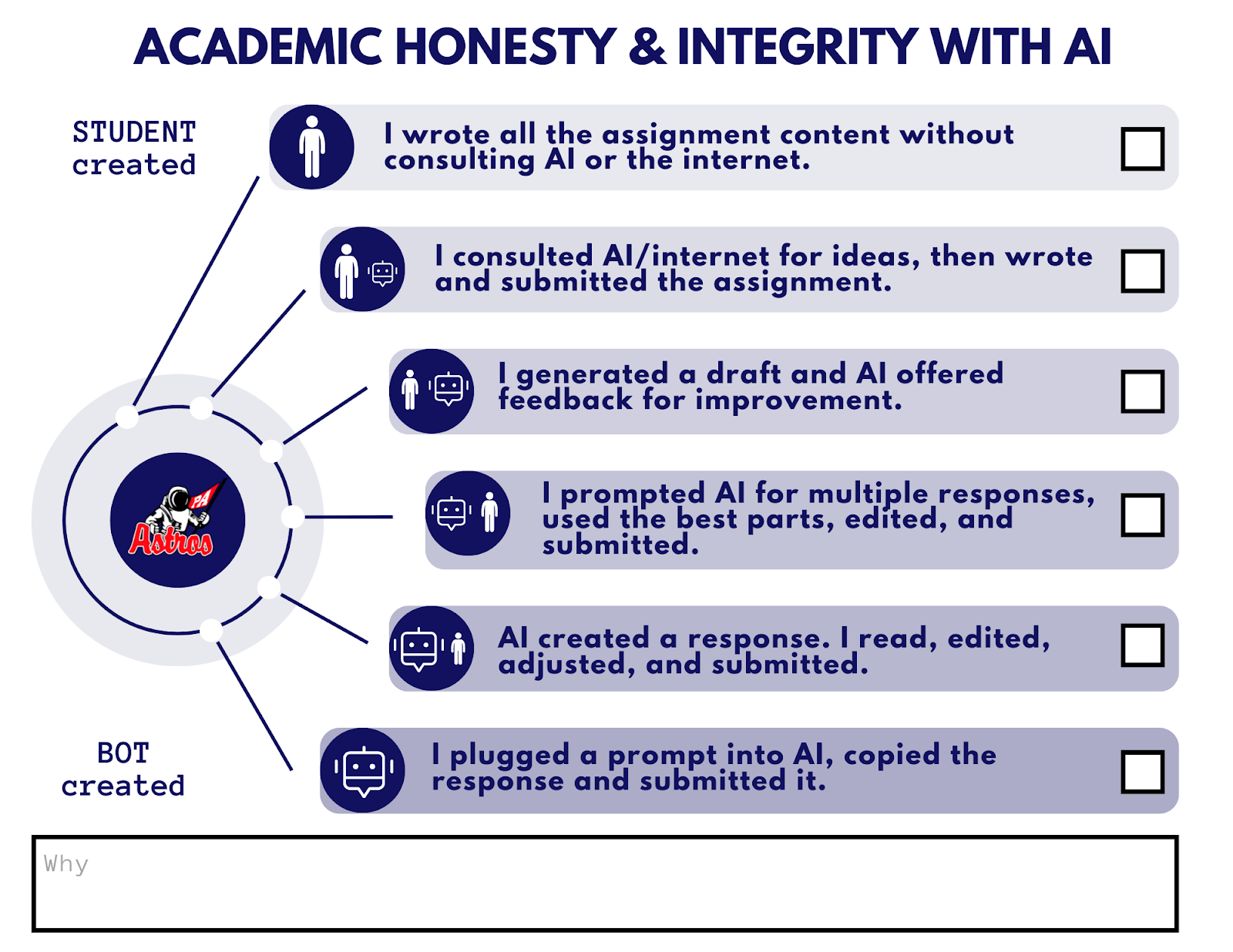

Christina DiMicelli’s Pinkerton Framework

One last alternative we include is a continuum system that encourages students to self-report, and allowing them to explain where their work falls on a spectrum of usage examples. This “continuum” model, designed and shared by Christina DiMicelli, Director of EdTech Learning & Growth at Pinkerton Academy, shifts to reflection rather than guardrails for students, which could foster more accountability, reflection, and honesty.

This model is also available for remix on Canva to suit your needs.

Agency, Accountability, and AI support in writing

It’s worth highlighting that the frameworks listed above are not by themselves an AI use policy, let alone pedagogical guidance. In the University of Sydney’s example, any “Lane 2” activity requires the student to add a critique of any AI output utilized, likely through a “Lane 1” type reflection. Adopted frameworks will see a variety of implementations across schools and among teachers. The landscape may appear patchy.

Over the summer, Helen Beetham wrote what will likely become a seminal essay on how AI makes us think of writing in an entirely new way. Writing as Passing finds a parallel between between writing and the Turing test: Looking at the final result and only from it making a judgement on whether there was any human involed.

In reality, writing as a practice has several implications, among other things on the development of authenticity, social expression, and identity. When it comes to writing, part of the policy must focus on helping students recognize the value of the process and skill development. By setting students recognizing the power and value of writing as the goal, we open up entirely new ways of addressing topics like authenticity and transparency, as well as AI as a threat.

Which begs the question: how do we make this possible? How can students find intrinsic value in their writing, and in their own process to becoming better and more comfortable at it? What is the best approach, or the ideal mix of approaches? Ultimately, answers may only come through experimentation.

There is some promising starting ground. Here are only some considerations that could help us piece together a better strategy:

- Since the pandemic, children and young people have reported an increased enjoyment in writing (PDF), according to the National Literacy Trust, particularly at home. During lockdowns they started writing more outside of coursework. The trends may have subsided, but a key insight in the report is a correlation between free time and voluntary, leisure writing.

- Writing has a well-researched mental health dimension, and constant practice considered effective management techniques for anxiety and depression at all levels. Inciting open-ended practice can help overall well-being, while guided writing on reflection and planning can help alleviate outstanding symptoms (PDF).

- According to Pew, teens know writing is important, although the 2008 study focuses on its economic prospects. Even since then, technology has been seen as a way to support writing practice. They see writing time during class as more beneficial than homework, and informal writing (such as texting) also a positive factor for their writing skills, even in formal and school contexts.

The takeaway, for now: leverage a clear and flexible policy, adopt and promote writing practice with varying levels (or “lanes”) or AI support; listen openly about student AI use in order to provide a better guidance on their use; and encourage both formal, guided writing, as well as informal writing on the student’s own time.

From policy to application

As the discussion on writing and the role of AI shifts from the product and after-the-fact evaluation to the process of writing, let’s focused on the student-centered outcomes that mirror the needs of modern education.

We have an opportunity to identify, share, and develop new policies, and implement tools that maintain transparency and trust. Moving away from writing as a static output—which AI has made obsolete—into a valuable activity, that is, a “practice” in its own right, can move the discourse positively and bring clarity to the classroom.

Writing continues to be a means of measuring and developing critical thinking skills and creativity. The next question is whether and how AI can play a role in enhancing the writing process. The same frameworks mentioned above has inspired some ideas:

- In project-based learning experiences, including complex writing projects (novels, dissertations), AI can help expedite planning and organization.

- Students may collaborate with AI by having it review their writing as a peer would. Important: Guide the AI thoroughly, with clear rubrics and plenty of examples.

- Teachers may leverage AI to suggest creative and guided writing activities and challenges. Have a voice talk with ChatGPT about how it could help you replace the type of assignments it is now able to do on behalf of the student.

- Students could critique a well-formed AI generated essay with track changes to ensure they recognize their own contributions vis-a-vis AI output.

- AI transcription might help with a tedious post-interview task to speed up a primary research project.

- AI could summarize a student essay to the most salient point to ensure the student has clearly identified their own point.

There are many examples of using AI responsibly in the student writing process. Complementary technology can further enhance the information about it, both for the students and for the AI tools. Writing analytics tools can offer verification, granular data, and writing patterns, to encourage habit formation, reflection and transparency. They allow you to see the student writing. No more Turing tests needed.

In Open LMS, the Cursive plugin provides writing process data and analytics that reflect a student’s drafting process to help instructors identify the authenticity of the writing effort. Cursive is flexible enough to support any of the above AI policy frameworks. Additional features include writing playback, pasted text highlights, pasted text comments from students, and more coming soon. While using the plugin through the LMS allows the teacher to access writing analytics for their students, Cursive also offers a Chrome extension. Any user can collect their own writing analytics by signing up for free and enabling on the sites or web applications they use for their writing practice.

To sum up

Transparency in the writing process could be best achieved through a concerted effort of policy, trust, and focus on the student process. In the age of generative AI, it’s best to assume that writing as just a product for evaluation is no longer a reliable path. (Add to it the fact that AI writing detection is ineffective and part of an “arms race.”) Writing as practice, with or without AI, coupled with analytics about the learner process, opens up entirely new possibilities.

For each of the above policies, the designers and adopters agree on several points:

- The value of this guidance can only fully be realized when it’s provided early and reiterated often to students in courses. Make sure that policies are clearly stated in course documents, in the learning management system, and reaffirmed periodically to help students meet all AI-usage expectations

- The frameworks provide more versatility than what we’ve expected from academic honesty statements in the past. “I hereby attest that this is my own work and no one else’s” is a more binary attestation of honesty. The various shades of AI used in the scales and frameworks above provide you and your students an assignment-by-assignment opportunity to change the rules of engagement.

- Trust but verify: guidance is only part of the equation. Setting expectations provides students advance notice, but having the tools to verify student work goes a long way in fostering trust and accountability in the classroom. Verifying academic integrity ensures a fair and level playing field for all students. Integrity tools and approaches vary (from proctoring to plagiarism to revision history) and may all have a place in the verification process for your assignments and assessments.

About the author

Joseph Thibault is the founder and CEO of Cursive, a new plugin for Moodle that is now available on OpenLMS. This first-of-its-kind approach provides writing process data and analytics to aid faculty in evaluation. Their ML/AI models verify student authorship through typing behavior. Cursive’s goal is to promote transparency in the writing process and remain flexible enough to support any of the above AI policy frameworks. Additional features include writing playback, pasted text highlights, pasted text student comments, and writing quality. More features are coming monthly.

For an example of Cursive’s approach to verifying student work along several AIAS aligned writing assignments, or a download of the Moodle-based course itself, please check out openlms.net/lms-extensions/cursive

Disclaimer: Cursive technology is a partner of Open LMS, owner of eLearn Magazine, to Ensure Academic Integrity in Student Writing. Learn more